Vol. 39 (# 23) Year 2018. Page 22

Vol. 39 (# 23) Year 2018. Page 22

Tatyana BONKALO 1; Anna RYBAKOVA 2; Aleksandra SHCHEGLOVA 3; Ekaterina KNYAZKOVA 4; Sergey BONKALO 5

Received: 26/02/2018 • Approved: 15/03/2018

ABSTRACT: The purpose is to identify the dynamics of the ethno-nationalistic sentiments of Russian and Ukrainian youth over the past 13 years, due to the media influence. The main method is the cross sections method with the use of both questionnaire methods and methods of psychological diagnosis. The materials allow disclosing the psychological nature of nationalism as a form of mass consciousness, to determine the educational and psychological mechanisms for the emergence and spread of nationalistic sentiments in the youth environment. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo es identificar la dinámica de los sentimientos etno-nacionalistas de los jóvenes rusos y ucranianos en los últimos 13 años, debido a la influencia de los medios de comunicación. El método principal es el método de secciones cruzadas con el uso de métodos de cuestionario y métodos de diagnóstico psicológico. Los materiales permiten revelar la naturaleza psicológica del nacionalismo como una forma de conciencia masiva, para determinar los mecanismos educativos y psicológicos para el surgimiento y la difusión de sentimientos nacionalistas en el entorno juvenil. |

One of the essential characteristics of the modern world is the use by the media of information and educational-psychological manipulation in order to create public opinion that is most beneficial to the state.

However, the desire to achieve a certain purpose with the help of hidden or distorted information can lead to the irreversible consequences for the state itself and for the individual.

One of such consequences is the formation of destructive national self-consciousness, which causes the growth of nationalistic attitudes and the formation of extremist and nationalistic sentiments, which turn into the birth of neo-Nazism and neo-fascism.

At its core, the origins of nationalism lie within the same limits of psychic reality as the origins of another, traditionally opposed to it, a massive psychological phenomenon - patriotism - namely, in the instinct of national self-preservation.

If we take into account the fact that in the modern world, in connection with the sharply escalated geopolitical situation, one of the priority tasks of any state is the task of activating patriotic feelings and emotions among its population: love for the Motherland, pride in it, awareness of the community of national interests, then the hidden information and educational-psychological influences used by the media for “noble purposes” may well have the opposite effect, because of the borders blurring and the common roots of patriotism and nationalism.

Suffice it to recall the pogrom committed by football fans in Moscow, for example, in June 2002. Quite a patriotic, according to the plan of the city authorities, an event with a collective viewing of the Russia-Japan match led to the fact that the center of the city for several hours was actually in the power of the brutal mob that had destroyed everything in its path. It is noteworthy that only in one episode, when several persons with a distinctly Asian appearance casually turned up by hand, the actions of pogromists can be reasonably interpreted as a manifestation of aggressive nationalism. Even more informative is the example of skinhead actions (Worger, 2012).

Such a “blurring” of the boundaries between nationalism and patriotism, at least in its ordinary sense, is by no means a specific feature of Russia, but rather universal.

It should be noted, for example, that at the first stages of his public political career, A. Hitler by no means called for a “final solution of the Jewish question” and, especially, the unleashing of another world war. In the relatively “vegetarian” period of his activity, the Führer of the German nation loved to speculate about the unique contribution of the German genius to European culture, the injustice of the Versailles system, the “double standards” of Western plutocracy, the need to protect compatriots who were outside the Reich, and other similar matters the corresponding factual amendments, the “calling card” of a number of “note” Russian “patriots”. Let us note that by 1939 there was no mention of any “vegetarianism” and, above all, precisely in the foreshortening of the problem of “patriotism-nationalism, Hitler: racial laws”, “night of broken glass”, concentration camps and so on.

It is important here that the precedent mentioned by us (far from being single) quite clearly indicates, in our opinion, a very disturbing trend - in the conditions of “increased demand” for patriotism and its ideological justification on the part of the state and a significant part of society, the development and implementation of relevant programs often turns out to be in the hands of incompetent and (or) unscrupulous representatives of the nomenclature, guided, above all, by opportunistic considerations.

One of the modern era tendencies that emerged after the collapse of the Soviet Union is the strengthening of ethnic self-awareness of peoples, but this increase leads to an increase in the differences between them (Bonkalo, Rybakova, Kolesnik, Shcheglova & Bonkalo, 2016). These natural processes become tools of information war and aggression, having their own political purposes and objectives.

It is surprising that, contrary to reasonable logic and universal morality, the country's multi-million population is ready to perceive any criminal acts as a manifestation of patriotism. For example, in Latvia, by a majority of votes on March 18, the day of the first Latvian region battle, the “Waffen SS”, organized on the personal orders of a convicted person worldwide A. Hitler, declared a state holiday; in Tallinn on May 19, 1999, the remains of the former commander of the 20th SS Division, Alphonse Rebane, were solemnly buried; in 1998, an anti-Semitic book entitled The Last Judgment was published in Latvia, published by Latvian fascists in 1942, edited by Heinrich Himmler (Bonkalo, 2014). The example of Ukraine with the general approval of the revision of the Second World War history, the renaming of streets and the erection of monuments to Stepan Bandera and the proclamation of it as a “national hero”, etc., confirm the urgency of the indicated problem and the identification of those psychological mechanisms that underlie the mass acceptance, in fact, of neo-fascist ideas and values.

The fact is that nationalism manifests itself primarily in the instinct of national self-preservation, and this instinct is inherent in everyone; it is on this instinct that the media is based, while conditioning the transformation and deformation of the individual.

In connection with the foregoing, we undertook a study whose main purpose was to reveal the psychological mechanisms of the destructive influence of the media on the national self-awareness of Ukrainian and Russian youth. Disclosure of such mechanisms was carried out based on revealing the dynamics of ethno-nationalistic sentiments of Russian and Ukrainian youth over the past 13 years.

Identifying the educational-psychological mechanisms of the media influence on the emergence and development of nationalistic sentiments among youth implies the disclosure of the psychological nature of nationalism itself as a form of mass consciousness.

Modern study emphasizes blurring and structural uncertainty in the use and interpretation of the “nationalism” notion. Thus, Miroslav Hroch (2015) points out differences in terminology and evaluation of nationalism by various scientific schools. Based on a various scientific ideas analysis, the author outlines five main features of nationalism, among which a special role belongs to the psychological manipulation used by the state through the information impact. Pelle Ahlerup & Gustav Hansson (2011), in the framework of economic study, discussing nationalism as an indicator of the success of the any state development, however, establish a negative relationship between the growth of nationalistic sentiments among the country's population and its economic well-being, thus raising the question of the destructive effect of actions the government on the development of patriotism on its effectiveness. Matthew C. Benwell (2014) points out that the desire to increase the interest of youth in their national culture and ethnic identity often turns into a surge of aggressive nationalism. On the example of the study of the nationalism manifestation in the secondary schools of Argentina and the Falkland Islands, the author, in fact, speaks about the blurring of the boundaries between positive and negative nationalism.

In modern studies, much attention is paid to the dissemination of nationalistic ideas in the countries of the former CIS. For example, Katrin Kello & Wolfgang Wagner (2014) in a study conducted in Estonian schools emphasize the impact of the interpretation of the historical past on the emergence of youth identity. The authors raise the question of the essence and ways of imposing the so-called “Estonian patriotism”. The object of the study Marlène Laruelle (2012) is the nationalism of Kyrgyzstan and the impact of explicitly nationalistic ideas on the development of the country. In modern studies, questions of nationalism are also studied in the relationship between the relations of different ethnic groups. Contemporary research also examines nationalism in relation to the relationship between different ethnic groups. Ingrid Griffiths & Richard Sharpley (2012) explore the impact of nationalism, its growth in various countries on the relationship of tourists and the host population. Rezarta Bilali, Ayşe Betül Çelik & Ekin Ok (2014), on the example of relations between Kurdish and Turkish communities, investigate mechanisms of intensification of conflicts and violence on national soil.

One of the controversial and controversial issues of the modern world is the question of the nationalistic sentiments growth among the youth of Russia and Ukraine. Studies devoted to this issue show ambiguity in the interpretation of the “nationalism” and “patriotism” concepts (Cannady & Kubicek, 2014; Enikolopov & Petrova, 2015; Kuzio, 2016).

The results of a theoretical analysis of modern concepts of patriotism and nationalism as forms of mass consciousness make it possible to draw two important conclusions. First, the most traditional is still the notion that patriotism presupposes positive feelings in relation to its not only people, but also tolerance towards another ethnos, whereas nationalism is based on intolerance of “alien” and the presence of aggressiveness, hatred and readiness for radical action. At the same time, patriotic and nationalistic ideas and attitudes have the same origins, which actualize the problem of identifying the mechanisms of their transformation into each other. Secondly, in the spread of nationalistic sentiments an important role belongs to the media, the information war that is unleashed in the world information space.

It should be noted here that the concepts of “information war” and “information aggression” as one of the means of conducting information and psychological confrontation have now become quite often used both in the media themselves and in specialized scientific literature. To date, there is a fairly clear idea of the essential and informative characteristics of the information war (Volkovsky, 2003, Pocheptsov, 2008, Blokh & Alexandrov, 2016) and information aggression (Greshnevikov, 1999), on ways to manipulate people's consciousness (Dotsenko, 1996, Grachev & Melnik, 1999), on the mechanisms of the media influence on their consciousness and psyche (Sheinov, 2004; Kara-Murza, 2005).

For example, V. Krysko (1999) emphasizes that the basis of information wars lies in the laws of psychological warfare, while psychological warfare is defined as the activity of special organs of the state to provide psychological influence on the civilian population in order to achieve certain political and military purposes (Bogatova, 2012).

Analysis of empirical data presented in a number of modern works (Levintova, 2010, Korostelina, 2013, Blokh & Alexandrov, 2016, Riabchuk, 2016), showed that a real information war has been launched between Russia and Ukraine lately. The results of the content analysis of news and political programs of the central television channels of Russia and Ukraine show that information about the same events that occurred both on the territory of the two countries and in the world as a whole is transmitted and interpreted in different ways, as a result which Russia appears in the Ukrainian media as an aggressive state, striving to dictate its terms and claims to recognize the exclusivity of its historical development (Blokh & Alexandrov, 2016); Ukraine appears in the Russian media as a state without a single national idea and a common identity, like a helpless society, where the authorities condone the “rampage of nationalism”, Russophobia and extremism (Korostelina, 2013).

During the past 13 years, we have been monitoring the change in the relations of the youth of Ukraine and Russia to each other. Such an observation was carried out in the process of study the national self-awareness of young people - students of leading Russian and Ukrainian universities. Samples were formed based on both the age criterion (20-22 years) and the criterion of respondents' use of the media as the main source of information. For this purpose, before the formation of study samples, students were asked about the regularity of viewing news and political programs on the central television channels of the country. The study samples included only those students who indicated that they monitor the events of domestic and international life every day or at least once every two days and use television as a source of information.

Thus, every three years, starting in 2004, a study was conducted in groups of students from Russian and Ukrainian universities. Each study sample consisted of 100 students, 50 of whom were boys, and 50 were girls between the ages of 20 and 22.

The diagnostic toolkit was selected based on the traditional concept of the structure of national consciousness as a relationship of its three main components: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. In this paper, let us dwell on the results of the study of the ethno-nationalistic attitudes of Ukrainian and Russian youth. For this purpose, both questionnaire methods (a specially developed questionnaire) and questionnaires were used, namely: “Types of ethnic identity” G.U. Soldatova and S.V. Ryzhovoy, the Kuhn-McPartland Test “Who am I?”, The scale of socio-psychological distance E. Bogardus.

The results of a comparative analysis of the ethnic identity types of Russian and Ukrainian youth indicate differences in the trajectories of its development. Cross sections in the groups of respondents showed that among Ukrainians a considerable number of such young people are characterized by hyperidentity (Table 1).

Table 1

Results of the study of ethnic identity types between Ukrainian and Russian youth

Types |

2004 |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

|||||

Russia |

Ukraine |

Russia |

Ukraine |

Russia |

Ukraine |

Russia |

Ukraine |

Russia |

Ukraine |

|

Ethno-nihilism |

8.45 |

8.05 |

9.35 |

8.15 |

7.85 |

6.95 |

7.65 |

3.05 |

6.35 |

2.25 |

Indifference |

9.95 |

8.90 |

10.15 |

9.35 |

9.40 |

8.75 |

8.25 |

6.15 |

7.95 |

5.05 |

Standard |

11.30 |

10.25 |

11.40 |

10.15 |

12.10 |

11.65 |

11.45 |

6.45 |

9.95 |

7.35 |

Ethno-egoism |

5.85 |

7.15 |

7.30 |

8.85 |

5.95 |

6.70 |

6.90 |

9.15 |

8.85 |

10.95 |

Ethno-isolationism |

4.35 |

4.05 |

4.90 |

10.45 |

5.05 |

5.35 |

5.65 |

12.95 |

5.70 |

9.30 |

Nationalistic fanaticism |

3.05 |

4.85 |

4.45 |

7.20 |

4.90 |

5.60 |

5.55 |

13.60 |

6.35 |

12.80 |

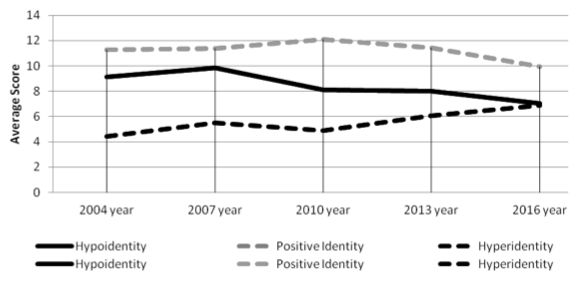

Attention is drawn to the fact that in the groups of Ukrainian youth the average group indicators of the degree of severity of hyperidentity have almost doubled, while the positive ethnic identity, assuming acceptance by the person of both their own and the other ethnic group, on the contrary, significantly decreased, compared with 2004. If in 2004, as well as in 2010, there were no significant differences between the two study groups, by the end of 2013 such differences were found in almost all the scales of the questionnaire.

In addition, it should be noted that the dynamics of the degree of severity of hypo-, hyper- and positive ethnic identity in groups of Russian and Ukrainian youth is by no means identical (Fig. 1, 2). Despite the general tendency for the growth of ethnic self-awareness in both groups, the awakening of interest in their national history and culture, which is manifested in a decrease in the degree of hypoidentity, in groups of Ukrainian youth the hyperidentity indicators significantly exceed the indicators of positive ethnic identity. The results of the study show that the majority of modern Russian students, despite the increase in ethno-egoism in comparison with previous years, are nevertheless characterized by a positive attitude towards their people, combined with tolerance to representatives of other ethnic groups. The majority of modern Ukrainian youth are distinguished by pronounced hyperidentity, conviction in the uniqueness of their people, the need to revive the national culture and get rid of “alien” elements, and those imposed from the outside traditions.

Fig. 1

Dynamics of the expression degree of ethnic identity types in the youth of Russia

-----

Fig. 2

Dynamics of the expression degree of ethnic identity types in the youth of Ukraine

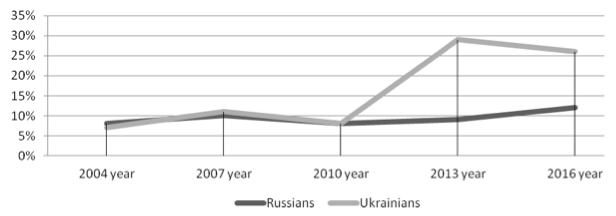

Interesting in this respect are the results of a study conducted using the methodology “Who am I?”. Respondents' answers were divided into 4 categories of analysis. In the samples of Russian students from 2004 to 2016, there were no significant changes in their self-identification. Approximately for the same number of respondents, who participated in 2004, and in 2007, and in 2010, and in 2013, and in 2016, is characterized by gender, social, role, professional, and ethno-cultural identification. In the group of Ukrainian youth, by 2013, the percentage of those who identify themselves in terms of civil, ethnic, and territorial characteristics has increased (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Dynamics of ethno-cultural identification of Russian and Ukrainian students

In groups of Russian youth, both in 2004 and in subsequent years, only 8-12% identify themselves as belonging to their people, which up to 2010 is also characteristic of Ukrainian students. However, by the end of 2013, more than 25% of Ukrainian students answered the question “Who am I?”: “Ukrainian”, “Kievan”, “Citizen of Ukraine”, etc. According to the results of the study, we can talk about the growing pride of Ukrainian students for their country and for the fact of belonging to it.

However, a subsequent study showed some ambivalence in the feelings of young people.

So, when answering the questionnaire: “What do you feel when you are called a Russian (Ukrainian)?” It was revealed that a sense of pride for your country is more characteristic of Russians than Ukrainians (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Results of the affective component study of national

self-awareness of modern Russian and Ukrainian youth (2016)

In the group of modern Russian youth, a sense of pride for belonging to one's own country, responsibility for its future prevails, whereas in the group of Ukrainian students, despite the consistently high rates of pride and responsibility, a sense of resentment and irritation. Resentment, as is known, is one of the latent aggression signs, in connection with which we can talk about the presence of many Ukrainians hatred and dislike - those negative feelings that are inherent attributes of nationalism. It is necessary to note one more fact. In the group of Russian youth, a high enough rank belongs to such a variant of the answer as “I do not feel anything”, which indicates a certain infalinity of Russians signs, their indifference to ethno-cultural issues. Among Ukrainian students, there are practically no indifferent, which indicates the actualization of ethnic and civic identity issues in the Ukrainian youth environment.

The feeling of pride, as is known, reflects patriotic attitudes. The study of the dynamics of the manifestation of a sense of pride for their country showed its growth in both the Russian and Ukrainian youth environment, moreover, the sense of pride among Ukrainians has increased dramatically since 2013. This fact served as a basis for further study on the ethno-national attitudes of the respondents of the two research groups. There were no significant differences between groups of Ukrainian and Russian students in terms of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. It is alarming that nationalistic attitudes are typical for a fairly large number of both Ukrainian and Russian students (32% and 38%).

As a result, we analyzed the results of a study of the socio-psychological distance, which young people with their own and other nationalities establish (Table 2).

Table 2

The results of the dynamics study of social acceptability

for Ukrainian and Russian youth of different ethnic groups

Ethnic groups |

Russians |

Ukrainians |

||||||

2004 |

2016 |

2004 |

2016 |

|||||

Russians |

+0.904 |

>50 |

+0.968 |

>50 |

+0.884 |

>50 |

-0.457 |

<50 |

Ukrainians |

+0.367 |

>50 |

+0.132 |

>50 |

+0.894 |

>50 |

+0.963 |

>50 |

Americans |

+0.002 |

>50 |

-0.567 |

<50 |

-0.176 |

<50 |

+0.437 |

>50 |

Representatives of Central Asia |

-0.539 |

<50 |

-0.793 |

<50 |

-0.777 |

<50 |

-0.811 |

<50 |

Representatives of the North Caucasus |

-0.471 |

<50 |

-0.773 |

<50 |

-0.576 |

<50 |

-0.818 |

<50 |

Representatives of the republics of Transcaucasia |

-0.603 |

<50 |

-0.711 |

<50 |

-0.782 |

<50 |

-0.766 |

<50 |

Germans |

+0.174 |

>50 |

+0.069 |

>50 |

-0.001 |

<50 |

+0.487 |

>50 |

French |

+0.198 |

>50 |

+0.114 |

>50 |

-0.003 |

<50 |

+0.034 |

>50 |

British |

+0.221 |

>50 |

+0.123 |

>50 |

+0.104 |

>50 |

+0.116 |

>50 |

Hungarians |

+0.044 |

>50 |

-0.188 |

<50 |

+0.696 |

>50 |

+0.861 |

>50 |

Serbians |

+0.406 |

>50 |

+0.675 |

>50 |

+0.713 |

>50 |

+0.455 |

>50 |

At the level of trends, we can say that over time, Russian youth are increasingly inclined to establish close and business relations only with people of their nationality. It is also interesting that, in comparison with 2004, the modern Russian youth negatively concerns Ukrainians. However, this fact is confirmed only at the level of trends: significant differences were not revealed. Socially unacceptable for Russian youth are marriage and family relations with Americans (significantly significant differences at a high level of significance). In the sample of Russian students, the indicators of the ability to establish positive relationships with people of other nationalities decreased. The most informed are the results of the obtained indicators analysis in the group of Ukrainian youth. Here we observe the transition from the zone of the positive to the zone of the negative choice of Russians and, on the contrary, from the negative to the positive choice of other nationalities.

The results of theoretical and empirical study have made it possible to identify the following mechanisms of the mass media influence on the emergence and development of nationalistic attitudes in the youth environment.

One of the psychological mechanisms of the information impact on a person is its relative deprivation, arising from a comparison of its position in the society with that which is constantly demonstrated in the media, and its unsatisfactory evaluation. The feeling that it is impossible to achieve the state and standard of living promoted in the media leads to the emergence and development of a young person's frustration, which is connected with the search for a way out of it through accusations of the “Other”. The desire for a “better life” becomes the basic need of young people, for which different methods are offered in the same media, including the use of violence and hatred of the prosecution object - the culprit of “all ills” and dissatisfaction with real life.

At the same time, the ideas of nationalism are born not only among low-income people, but also, as the examples of history show, among people who are sufficiently wealthy and educated. Here there can be a phenomenon of permissiveness associated with hedonistic values and life purposes. The need for permissiveness implies the desire to overcome any conventions and limitations, up to the rejection of universal morality and morality.

The main reason for the emergence and spread of nationalistic sentiments in the youth environment, caused by the impact of the media on their national identity, is the identity crisis that began in the CIS after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Identity implies the establishment of a close emotional connection within the community. Today, there is scientifically valid information that the inclusion of a person in an emotionally interrelated group causes the loss of his individuality, due to the actualization of the same for all members of the collective unconscious group. The subject of activity, with all its individuality and originality, is transformed into a “mass individual”. “Mass individual” becomes suggestively vulnerable: he begins to perceive the information transmitted to him without any analysis and criticism. This perception of information has a decisive influence on the neuropsychic and somatic processes that determine the increased suggestibility of the “mass individual” and its dependence on the leader, the leader of the group.

Another psychological mechanism for the development of nationalistic sentiments under the influence of the media is the substitution mechanism, often used by group leaders to rally their members. The mechanism of substitution, in fact, is the process of reorienting the negative emotions of a person to external purposes. Meanwhile, members of one community establish warm, truly fraternal relationships based only on positive emotions. Human feelings of hostility, hatred are redirected to other objects - on “alien”, “guilty”, “different from us”, “unclean”, “infidels”, etc. Relationships within the community are all the stronger, the greater and stronger the hatred of external objects. Here there is another basic need of man in harmonious and warm relations with other people. Satisfaction of this need is carried out in rallying people against one “enemy” and in achieving a common purpose.

Beginning in 2013, the Ukrainian media, supporting the foreign policy of the new Government, interpret the facts in its interests, in connection with which Russia as a state appears to the Ukrainian people as an aggressor. Therefore, we should talk about the formation of nationalistic attitudes in the conditions of information war. We see the same tendencies on the example of Russian youth, and therefore, we need to find ways to block the mechanisms of the destructive influence of the media on the national self-awareness of youth.

The publication was prepared within the framework of the scientific project No. 15-06-10966 “Psychological mechanisms of the transformation of patriotism into nationalism in conditions of information aggression” supported by the Russian Humanitarian Scientific Foundation.

AHLERUP, P., HANSSON, G. Nationalism and government effectiveness. Journal of Comparative Economics. Vol 39, year 2011, number 3, page 431-451.

BENWELL, M. From the banal to the blatant: Expressions of nationalism in secondary schools in Argentina and the Falkland Islands. Geoforum. Vol 52, year 2014, page 51–60.

BILALI, R., ÇELIK, A.B., OK, E. Psychological asymmetry in minority–majority relations at different stages of ethnic conflict. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. Vol 43, year 2014, number B, page 253–264.

BLOKH, I., ALEXANDROV, V. Psychological Warfare Analysis Using Network Science Approach. Procedia Computer Science. Vol 80, year 2016, page 1856-1864.

BOGATOVA, E.B. To the question of the socio-psychological prerequisites for a person's susceptibility to verbal influence. Izvestiya Penza State Pedagogical University named after Belinsky. Vol 28, year 2012, page 1152-1153.

BONKALO, T.I. Psychological mechanisms of the transformation of patriotism into nationalism: formulation of the problem. Human capital. Vol 6, year 2012, page 13-22.

BONKALO, T.I., RYBAKOVA, A.I., KOLESNIK, N.T., SHCHEGLOVA, A.S., BONKALO, S.V. Individual psychological characteristics of members of destructive religious and ethno-nationalist organizations. Indian Journal of Science and Technology. Vol 9, year 2016, number 46, page 107514.

CANNADY, S., KUBICEK, P. Nationalism and legitimation for authoritarianism: A comparison of Nicholas I and Vladimir Putin. Journal of Eurasian Studies. Vol 5, year 2014, number 1, page 1-9.

DOTSENKO, E.L. (1996). Psychology of manipulation: phenomena, mechanisms and protection. Мoscow: Moscow State University.

ENIKOLOPOV, R., PETROVA, M. Chapter 17: Media Capture: Empirical Evidence. Handbook of Media Economics. Vol 1, year 2015, page 687-700.

GRACHEV, G., MELNIK, I. (1999). Manipulation by personality: organization, methods, and technology of information and psychological impact. Moscow: RPANEPA.

GRESHNEVIKOV, A. (1999). Information war. Мoscow: Russian world.

GRIFFITHS, I., SHARPLEY, R. Influences of nationalism on tourist-host relationships. Annals of Tourism Research. Vol 39, year 2012, number 4, page 2051-2072.

HROCH, M. Nationalism, Historical Aspects of: The West. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition). Year 2015, page 283–289.

KARA-MURZA, S. (2005). Manipulation of consciousness. Мoscow: Eksmo.

KELLO, K, WAGNER, W. Intrinsic and extrinsic patriotism in school: Teaching history after Estonia's critical juncture. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. Vol 43, year 2014, number A, page 48-59.

KOROSTELINA, K.V. Ukraine twenty years after independence: Concept models of the society. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 46, year 2013, number 1, page 53-64.

KRYSKO, V. (1999). Secrets of psychological warfare. Minsk: Bauman Moscow State Technical University.

KUZIO, T. Soviet and Russian anti-(Ukrainian) nationalism and re-Stalinization. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 49, year 2016, number 1, page 87-99.

LARUELLE, M. The paradigm of nationalism in Kyrgyzstan. Evolving narrative, the sovereignty issue, and political agenda. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 45, year 2012, number 1-2, page 39–49.

LEVINTOVA, E. Past imperfect: The construction of history in the school curriculum and mass media in post-communist Russia and Ukraine. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 43, year 2010, number 2, page 125-127.

POCHEPTSOV, G. G. (2008). Information war. Мoscow: Eksmo.

RIABCHUK, M. Ukrainians as Russia's negative ‘other’: History comes full circle. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 49, year 2016, number 1, page 75-85.

Sheinov, V. (2004). Hidden control of man: psychology of manipulation. Мoscow: AST.

Volkovsky, N. (2003). The history of information wars. St. Petersburg: Speech.

WORGER, P. A mad crowd: Skinhead youth and the rise of nationalism in post-communist Russia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 45, year 2012, number 3–4, page 269-278.

1. Russian State Social University, Russia

2. Russian State Social University, Russia. rybakova.anna2018@yandex.ru

3. Russian State Social University, Russia

4. Russian State Social University, Russia

5. The Moscow State University of Design and Technology, Russia